June 11, 2024

📰 FEATURE STORY

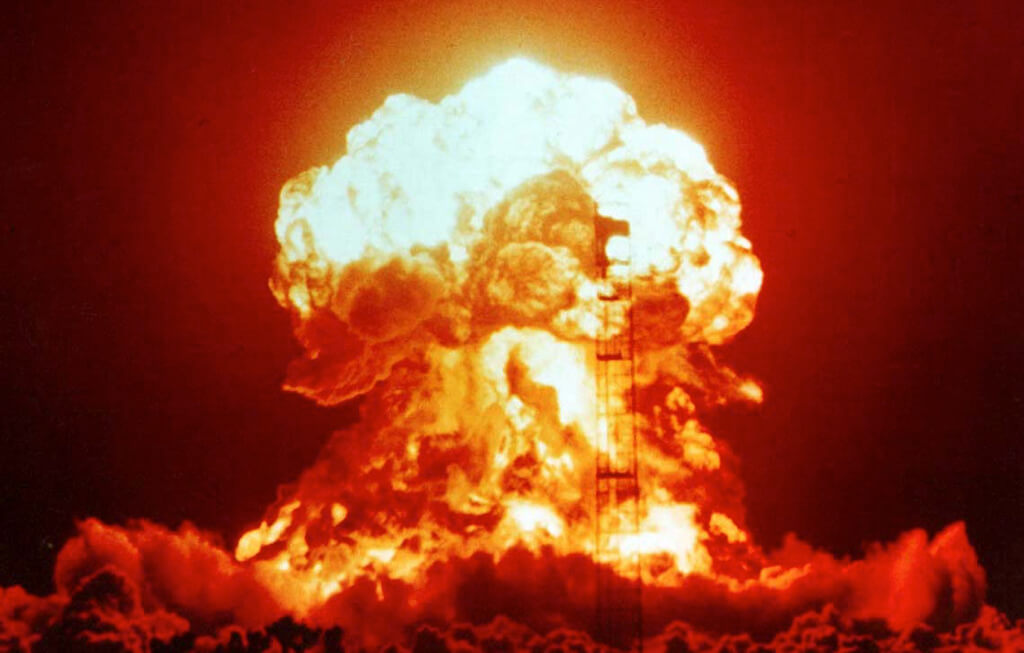

Will a worldwide no-first-use rule on nuclear weapons work?

J Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, was a complicated figure. After his work on The Gadget, as the bomb was dubbed, was done, he and his fellow scientists debated civilian and military officials to try and restrain an arms race they predicted would happen. They argued for arms control and eventual disarmament.

Decades later, the world continues to grapple with those issues. With Vladimir Putin threatening nuclear strikes as retaliation during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the issue has flared up. Most recently, China called for some control on the use of nuclear weapons. Earlier this year, it proposed all nuclear weapon states agree on a treaty of no first use against each other. While this sounds good and necessary on paper, can it work in practice?

Context

Most states that have nuclear weapons keep policies in place that would allow their first use in a conflict. A no-first-use pledge was first publicly made by China in 1964. Simply put, it refers to any statement by a nuclear weapon state to not be the first to use them in a conflict and strictly reserve the right to retaliate in the aftermath of a nuclear attack against its territory.

Along with China, India was the only other country to adopt such a pledge. In the West, things are complicated, given its tumultuous history. During the height of the Cold War, the threat of the US using a nuclear weapon was a critical bulwark against a Soviet offensive through a lowland corridor in Germany called the Fulda Gap. While the US has considered a no-first-use policy, it hasn’t officially declared it. It’s also the only country to ever use nuclear weapons in war.

A first-use policy was seen as arguably the best defensive strategy for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). There was something of an arms race going on. Between 1945 and 1992, the US and Russia conducted over 1,700 tests in the atmosphere and underground. Other nuclear states conducted 311 tests until 1998. During the Cold War, tests were the cornerstone of nuclear weapons development.

This was also the time when antinuclear advocates thought a ban on testing would be the best way to stop, or at least, lessen the pace of an arms race. The fruits of their labour were perhaps fulfilled in 1996 when the UN adopted the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). It was signed by the nuclear weapon states of China, France, Russia, the UK, and the US, along with 66 other countries.

As far as India is concerned, 50 years since the historic Pokhran I test, India has emerged as a regional and global player. Ever since that day in 1978 when India announced itself as a nuclear-capable country to the world, its nuclear ambitions grew. But India also adopted a no-first-use doctrine in 2003.

China put forward a new no-first-use treaty at the United Nations Conference on Disarmament in February. Given the complicated and often paradoxical nature of nuclear strategy, would such a treaty be feasible today?

VIEW: It can be done

At the outset, it’s understandable to be sceptical about China’s intentions. However, China has always maintained its no-first-use doctrine, and a global treaty makes more sense than any other arms control framework proposed. Some may argue it’s unrealistic to expect countries to give up weapons in any way, not the least when there’s an ongoing war in Europe perpetrated by Russia. But that’s why this treaty makes sense since it’s better than the status quo and moves the conversation in the right direction.

The nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT) system has largely failed. The only reason it’s continuing to exist is in the interest of a handful of countries that use it to claim they’re legitimate nuclear powers. To get technical and into the semantics for a moment, a treaty could begin with banning nuclear landmines, neutron bombs, and other similar weapons to build confidence among stakeholders. The treaty could also raise the stakes and make even verbal threats of using nuclear weapons as a violation.

This no-first-use treaty would also be in India’s best interest and would signal to the region and the rest of the world that such a policy is feasible. If China does invite India to participate in the talks, then the world will know this treaty is legit. While a global no-first-use treaty won’t necessarily solve the nuclear issue overnight, it’s a good first step.

COUNTERVIEW: Easier said than done

To begin with, there’s all the reason in the world to be suspicious of China’s intentions with this treaty. By most accounts, China’s nuclear inventory has continued to grow with some estimates putting it at over 500 warheads with more on the way. It’s projected to be 1,500 by 2035. While it does maintain a no-first-use doctrine, there’s very little known about its nuclear capabilities and modernisation ambitions.

Some opponents of a no-first-use policy have pointed out that a nuclear state is a secure state. Nuclear weapons give a state absolute security as countries become more militarised. It’s the basic motivation for countries like the US and China to keep warheads. Coming to India, there’s no doubt that a one-on-one military conflict would be lopsided since India’s armed forces, capable as they are, aren’t on par with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has changed the military equation across Europe. NATO and European countries are arming themselves at a rate not seen in decades. Given all this, a no-first-use treaty doesn’t seem like a possibility. It’s why countries like France, which rejoined NATO in 2009, decided to keep its nuclear forces outside of NATO’s defence coordination mechanisms.

Reference Links:

- China urges largest nuclear states to negotiate a ‘no-first-use’ treaty – Reuters

- ‘No First Use’ and Nuclear Weapons – Council on Foreign Relations

- 50 years since Pokhran I, does India need to look at reviewing its nuclear doctrine? – The Week

- By the numbers: China’s nuclear inventory continues to grow – The Lowy Institute

- India’s nuclear doctrine is useless. Discard no-first-use, say nukes are for China threat – The Print

- Why a substantive and verifiable no-first-use treaty for nuclear weapons is possible – Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

- It’s Time to Talk About No First Use – Foreign Policy

What is your opinion on this?

(Only subscribers can participate in polls)

a) A worldwide no-first-use rule on nuclear weapons will work.

b) A worldwide no-first-use rule on nuclear weapons won’t work.

🕵️ BEYOND ECHO CHAMBERS

For the Right:

How strident Hindutva dented BJP and allies in the North East

For the Left:

How re-energised focus on ‘Neighbourhood First’ under Modi 3.0 can work wonders