March 7, 2023

Good morning. In today’s either/view, we discuss whether India has the ability to effectively implement a One Health policy. We also look at schools being denotified in Himachal Pradesh, among other news.

📰 FEATURE STORY

Can India effectively implement a One Health Policy?

At the end of every disaster awaits a lesson. The terrible toll that COVID-19 had on people’s lives, health, jobs, and happiness was an eye-opener for many. In several countries, researchers and policymakers began looking for ways to fix their healthcare systems and prepare them for deadlier pandemics in the future. During a Health and Medical Research webinar, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently announced the One Earth, One Health mission.

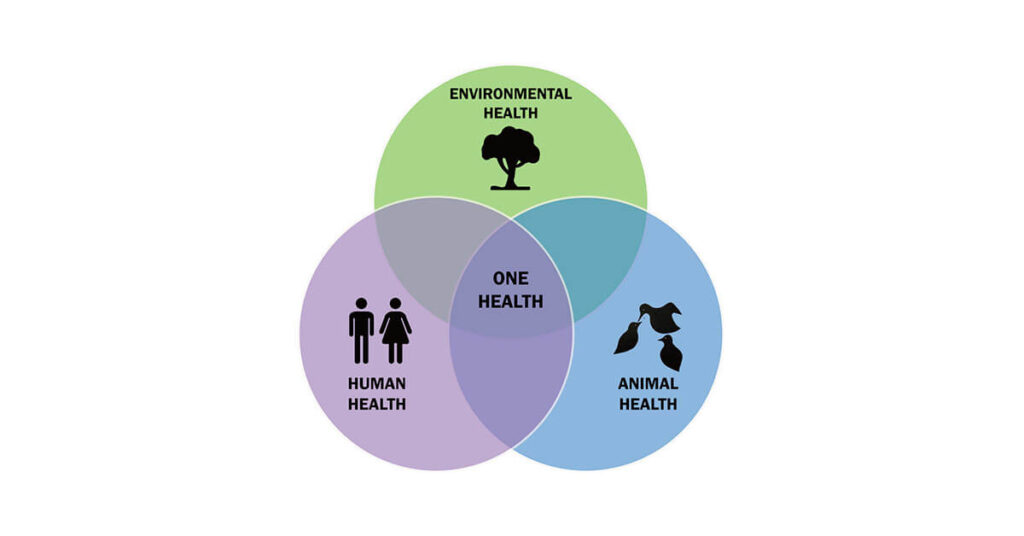

A One Health (OH) approach emphasises the interconnected well-being of humans, animals, and ecosystems. Healthcare infrastructure and workers certainly need a holistic fix than a temporary bandaid, which such a mission offers. But whether an OH Policy is practicable remains murky given the past failure of other universal healthcare missions.

Context

Virologists and epidemiologists find that the COVID-19 pandemic began due to at least two zoonotic spillovers from animals sold at the Huanan market. “Not a lab, not a cave, not a dentist’s office,” said Dr Angela Rasmussen.

Pathogens originating in animals cause around 60% of infectious diseases and 75% of all emerging infections. Besides, antibiotic-resistant microbes can spread from animals to humans and cause illnesses that conventional antibiotics can’t cure.

Humans’ use of antibiotics is, more often than not, irrational. And we’ve spread the problem to our livestock by using them to increase yield and prevent diseases. Eventually, this leads to the emergence of resistant pathogens that spread through the human-animal food chain.

But it’s not just diseases that underscore the interconnectivity between humans, animals, and the environment.

Healthy and symbiotic ecosystems improve collective well-being and climate change impact. Respectful relationships with animals and plants, which form the basis of many traditions in India, help cure diseases, improve social interactions for people with autism, and decrease cortisol levels in humans.

To make use of our interconnectivity rather than let it be a downer, experts advise devising an OH Policy that optimises the well-being of all actors in the ecosystem. If these relationships or one of the actors in this value chain deteriorates, it adversely affects everyone.

In India, the PM’s Science, Technology, and Innovation Advisory Council (PM-STIAC) recommended a ‘One Health Mission’ to design a unified pandemic preparedness plan cognisant of technology and policy-level interventions across human, livestock, and wildlife sectors. The government’s OH mission also seeks to combine all previous OH initiatives under one umbrella.

In the past, the Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying (DAHD) backed OH pilots in Karnataka and Uttarakhand to help design a national framework. Growing demand for seafood compelled fishery scientists from India and the United Kingdom to call for an Indo-UK partnership to implement a One Health Aquaculture concept in India.

An OH infrastructure is brought to life by the close multisectoral collaboration of policymakers, health experts, environmentalists, and national and international leadership. To this end, the United Nations devised a multilateral pandemic treaty that will serve as an international instrument to enforce a “whole-of-government” and “whole-of-society” approach.

While it is reasonable to be optimistic about the wonders of OH, its implementation requires a serious commitment from national leaders and a substantial overhaul of current approaches to healthcare in India.

VIEW: The wheels are oiled and the sails set

Initiatives like the pandemic treaty have sensitised leaders across the globe to an expected paradigm shift in health infrastructure and policies following the COVID-19 years. In India, with the breaking point of healthcare and climate came the realisation that existing gaps in OH need to be identified and inter-sectoral collaboration strengthened. The Karnataka and Uttarakhand OH pilots did precisely that.

Uniting the various OH initiatives spread across the wildlife, health, and climate sectors will help consolidate the current solutions-based approach of the government to a preventive one. The National Health Mission (NHM) and the Prime Minister’s Atmanirbhar Swasth Bharat Yojana (PM-ASBY) schemes can help allocate budgetary and human resources for intersectoral coordination.

The current synergy of national governments, India’s G20 Presidency, and Bill Gates’ enthusiasm have shaped a favourable momentum for an all-around focus on OH. In a recent interaction with the Principal Scientific Adviser to the Government of India, Gates was interested in supporting India’s OH Mission through animal vaccines and open-source disease modelling, among other things.

COUNTERVIEW: A focus on the basics is lacking

The scope of an OH policy to work has several design and implementation hurdles to overcome before being imaginable. In India, while the Union government’s policies act as guiding directives, ensuring effective enforcement is the state governments’ prerogative – binding the healthcare system in a highly hierarchised and polarised environment.

The entire practicability of OH rests on effective collaboration. But the siloed existence of focal health, animal science, wildlife, and environmental agencies renders cross-sectoral differences a colossal task. Human health experts compose most of the National Standing Committee on Zoonoses, leaving animal science and wildlife experts on the fringe.

In the current public health and disease prevention setting, zoonotic diseases have limited policy visibility and expression. The National Livestock Programme (NLP) 2013 recognises them but fails to specify mechanisms to prevent, control, or eradicate them. India needs to go back to the basics first and improve funding, policy support, and representation of diverse experts in health institutions to enforce a One Health policy.

Reference Links:

- Karnataka among two States to host One Health pilot with focus on zoonotic diseases – The Hindu

- Is India’s One Health moment on the horizon? – Financial Express

- One Health: What it is & how it can be implemented in India – Down to Earth

- Operationalising the “One Health” approach in India – BioMed Central Ltd

- Overcoming challenges for designing and implementing the One Health approach – NCBI

What is your opinion on this?

(Only subscribers can participate in polls)

a) India is equipped to implement a One Health policy successfully.

b) India is ill-equipped to implement a One Health policy successfully.

🕵️ BEYOND ECHO CHAMBERS

For the Right:

Nagaland Crisis: Three Elections Later, Can BJP Stand True To Its Peace Promise?

For the Left:

Why India is in the vortex of global geopolitics as world affairs increasingly become fluid

🇮🇳 STATE OF THE STATES

Schools with zero students denotified (Himachal Pradesh) – The government of Himachal Pradesh has denotified a total of 228 primary schools and 56 middle schools having zero students enrolled in them. Staff members, both teaching and non-teaching, appointed in these schools will be transferred to those with a staffing deficit. There are 455 elementary and secondary schools that operate with deputised personnel because they lack regular staff. The government also found that around 3,000 primary schools in the state have only one teacher, and over 12,000 teacher posts are lying vacant.

Why it matters: Around 380 of these schools had been opened in the previous 4-5 months during the tenure of the BJP. Only 21% of all the schools meet satisfactory admission numbers. The government is planning to overhaul the system of schools in the state by redefining the criteria for opening schools and managing the movement of teachers in the state. The government aims to improve both the quality as well as the outreach of education in the state.

High yield, low price: A baneful harvest (Telangana) – Red chilli farmers in Warangal have been successful in raising a bumper yield of red chillies. However, this has become a source of disappointment instead of happiness. These farmers are now being exploited by traders who are forcing them to sell their produce at very low prices. Farmers are getting a mere ₹21,700 per quintal instead of the displayed market price between ₹27,500-35,000 per quintal.

Why it matters: The farmers are expressing anger as well as grief towards the situation. According to the farmers, the minimum support price is not being followed, and the market yard officials responsible for maintaining order and fairness are in cahoots with the traders. The farmers are saying that they are unable to get a good price even for the varieties of red chillies that are in high demand.

Farmers opting for open markets (Odisha) – A growing number of farmers in Odisha are bypassing traditional agricultural mandis to sell their produce directly to consumers or wholesale buyers in the open market. This shift is driven by several factors, including a desire for better prices and more flexibility in the sales process. The biggest reason, however, according to farmers, is the harassment faced by the farmers at the mandis. Some farmers also report that they have been able to reduce their transportation costs and increase their profits by selling directly to buyers in nearby cities or towns.

Why it matters: Mandis have long been a cornerstone of the Indian agricultural system, providing a platform for farmers to sell their crops and connect with buyers. However, in recent years, mandis have faced criticism for their lack of transparency, high transaction costs, and limited competition. Moreover, farmers are also alleging that mandis don’t follow the MSP anyway. Hence, the open market is more beneficial to them. This shift can tackle the inefficiencies and improve price discovery in the agricultural sector, ultimately benefiting farmers, consumers, and the wider economy.

15 companies facing financial distress (Rajasthan) – The Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) has reported that 15 companies in the state of Rajasthan have suffered a complete erosion of their net worth. This means that the companies’ liabilities have exceeded their assets, leaving them with a negative net worth. According to CAG’s recently published report, the decrease in profit was primarily caused by the cessation of funding provided to state discoms under UDAY, which was only in effect from 2019–20.

Why it matters: The CAG’s analysis also showed that 15 SPSEs had totally lost all of their net value. According to the CAG, investment and accumulated losses for the year 2020–21 revealed that net value was completely lost in 15 of the 41 SPSEs as capital investment and accumulated losses were ₹33754.35 crore and ₹96491.58 crore, respectively. Four power industry firms, including JdVVNL, JVVNL, AVVNL, Giral Lignite Power Ltd (GLPL), and Rajasthan State Road Transport Corporation, experienced the greatest net value erosion of the 15 SPSEs.

Moidams nominated for UNESCO World Heritage Site (Assam) – From a selection of 52 locations nationwide, the Union government chose the “Moidams” as India’s sole submission for the Unesco World Heritage Site designation for 2023–2024. The Moidams in the Charaideo district are the final resting place of the royal families of the Ahom empire of Assam.

Why it matters: The proposal for UNESCO World Heritage Site status is important because it would bring global recognition and protection to the royal burial grounds, which are currently under threat from urbanisation and encroachment. It would also boost tourism in the region, creating economic benefits for local communities. Furthermore, the Ahom dynasty and their burial sites represent an important part of India’s history and cultural heritage.

🔢 KEY NUMBER

84 – There were 84 instances of internet shutdown in India in 2022, the highest across the world.